Criticism can be like a bee, it hurts when your stung, you have a mark for days, and sometimes you might even have a big allergic reaction. Criticism can also be like a teacher or coach, giving you productive feedback. Given at the right time, from the right person, with the right delivery, it can propel you forward.

In my work, a theme that comes up over and over again is how in relationships, we’re so often trying to be that second critic. The coach, the teacher, to help our loved ones, but what we often come off as is the bee.

Here is the story of a fictitious family, based on real clients and my real interactions with those clients.

A family of two parents, one teenage son, and another school aged daughter came into my office. Their son had been skipping class and his grades had dropped significantly. The parents immigrated to the US based on their academic achievements, so school performance was highly valued in their family. After the intake, I split up the son and parents to gather more information. When it was just me and the parents, they proceed to tell me, in twenty different ways, how great their son was. Their frustration and anger were rooted in their strong belief that he could make different choices. “If he only applied himself, he could be valedictorian!”

When I talked to the son, he was angry at his parents and his rebellious behavior felt good in the moment. However, he was a good kid and when he came down from the high of the rebellion, shame flooded him, and fed a growing feeling of anxiety and depression. He wanted to do better at school, but he didn’t think he was smart enough or had the ability to work hard enough to get the grades he wanted. His internalized beliefs in himself, felt almost in complete opposition to his parents’ beliefs in him. The disconnect was big and felt important.

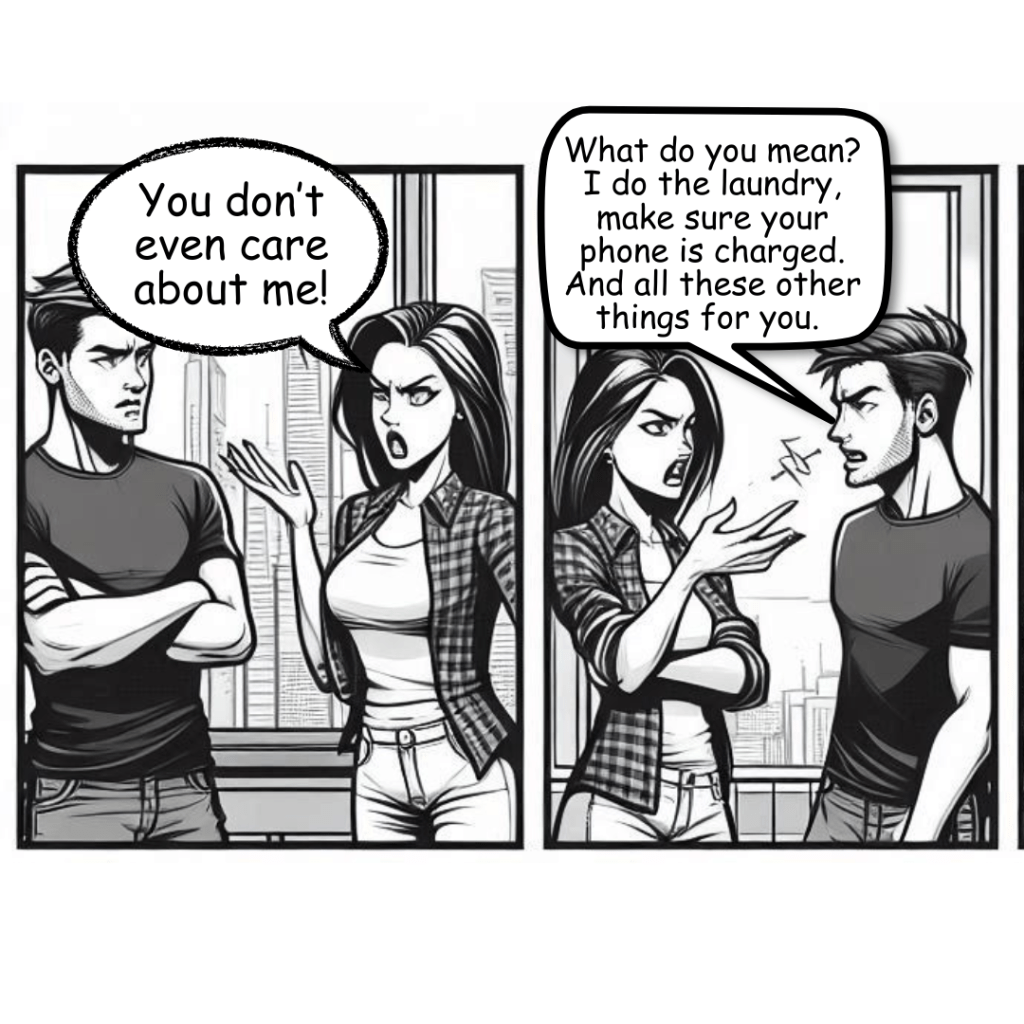

Within 10 minutes of our next session, everything made sense. These were not the same parents who I talked to last session. In front of their son, all they seemed capable of, was criticizing him. “You don’t work hard enough.” “You never wake up early enough for school.” “Why aren’t you more like your sister.” No wonder their son had such strong negative self-talk. He was internalizing the messages he was hearing. At some point, his parents’ criticism turned into his own voice.

As a family therapist, I try to make implicit relational communication explicit. Trying to get the parents to set the record straight, I voiced my confusion. “I thought you told me he has so much potential? Listening to you now, I would think you don’t believe in him?” As the session unfolded, they explained how their criticism was their attempts to get their son to change his behavior. Their belief in him drove their criticism and they felt like this was support.

Here it was again, criticism as misguided support.

The Research

In the Gottman research on relationships, criticism is defined as an attack or blame on the persons character not behavior1. In high dosage, it is one of the four killers of relationships. It is often communicated in the form of “you shouldn’t have…” “you always…” suggesting that it is not the persons choices that deserve the criticism but the person themselves is bad. The Gottman research calls out how criticism is often a wish or a want for connection in disguise. It’s a negative expression of a need within the relationship1.

One of the natural responses to criticism is defensiveness, another one of the 4 killers of relationships1. When a person is defensive, they are closed off, often falling into a fixed mindset of the situation2. In that closed off or suppressed state, feelings of contempt or disgust increase and closeness or care decrease2. Quickly, the communication within the relationship can turn into a negative cycle that spirals out of control.

As I explained the Gottman research to the family, I was met with a common question. “Does that mean we can’t say anything?” “How are we supposed to say what we think?”

It turns out, perception is what determines if criticism is productive or a killer2. If the person receiving the criticism views it as hostile, it has the negative effect that the Gottman research explained. However, if the criticism is viewed as constructive, it can actually improve relationships2. I think of my favorite high school English teacher Mrs. Teson. There was a lot of critical feedback in our student/teacher relationship but, she made me feel valued. I believed she wanted to help me, so her criticism felt constructive.

Even when given tactfully, sometimes the person receiving the criticism is not yet ready to see the criticism as constructive. Perhaps there is too much history, or too much repair that needs to happen. In those cases, it is better to find an alternate means of support or sometimes, say nothing. In parent child studies, parental criticism is associated with “anger, anxiety, shame, and sadness”3. More emotional labor is put on the child or teen, who simultaneously is trying to achieve their goals and hold the negative outcomes from their parents’ criticism.

In the case of the family, the research shows that it is ok to have high standards4. However, when criticism is used to motivate or “support” that standard, it has the negative effect of focusing the teen on the mistakes they make instead of orienting them towards their goals. Said another way, the teen is more likely to get frozen in their mistakes when critical voices are high versus working through the mistakes to achieve their goal.

Changing How We Think Gives Us Control

So what if the parents in my family could not or did not want to change? Was my teen destined to stay frozen, escalating his rebellious behavior?

The short answer is no. Helping my teen understand his parents’ underlying intent of their criticism was powerful. Changing his interpretation of his parents helped him change his emotional response. When he felt more in control of his emotions, he could choose his response. Sometimes it was to engage and get curious. Sometimes it was exiting the conversations without an escalation. My teens experience is supported in the data. A cognitive reappraisal or reframe of the situation can lead to “positive emotions, positive expression, increased perception of closeness, better social problem solving, and greater perceptions of caring behaviors from parents”2.

Moving forward, my work with the family would center around changing communication patterns and diving deeper into the disconnects that fueled these patterns. I learned from my clients that when facing criticism as misguided attempts of support, changing how we think about that criticism gives us power. It takes us out of the victim stance and into the driver seat. I wonder if we could even apply these learning with our own inner critic. Getting curious about what is their motivation? What are they trying to support? Can these learnings help us start the journey of compassionately reteaching our inner critic a different way of communication, breaking that cycle within ourselves.

References

- The Gottman Institute. The Four Horsemen: Criticism, Contempt, Defensiveness, and Stonewalling. The Gottman Institute. https://www.gottman.com/blog/the-four-horsemen-recognizing-criticism-contempt-defensiveness-and-stonewalling/

- Klein, S. R., Renshaw, K. D., & Curby, T. W. (2016). Emotion regulation and perceptions of hostile and constructive criticism in romantic relationships. Behavior Therapy, 47(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2015.10.007

- Zhu JY, Simons JS, Goldstein AL. Dynamics of parental criticism and emerging adult emotional functioning: Associations with depression. J Fam Psychol. 2022 Dec;36(8):1451-1461. doi: 10.1037/fam0001022. Epub 2022 Aug 4. PMID: 35925715.

- Madjar, N., Voltsis, M., & Weinstock, M. P. (2015). The roles of perceived parental expectation and criticism in adolescents’ multidimensional perfectionism and achievement goals. Educational Psychology, 35(6), 765–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.864756

Leave a comment